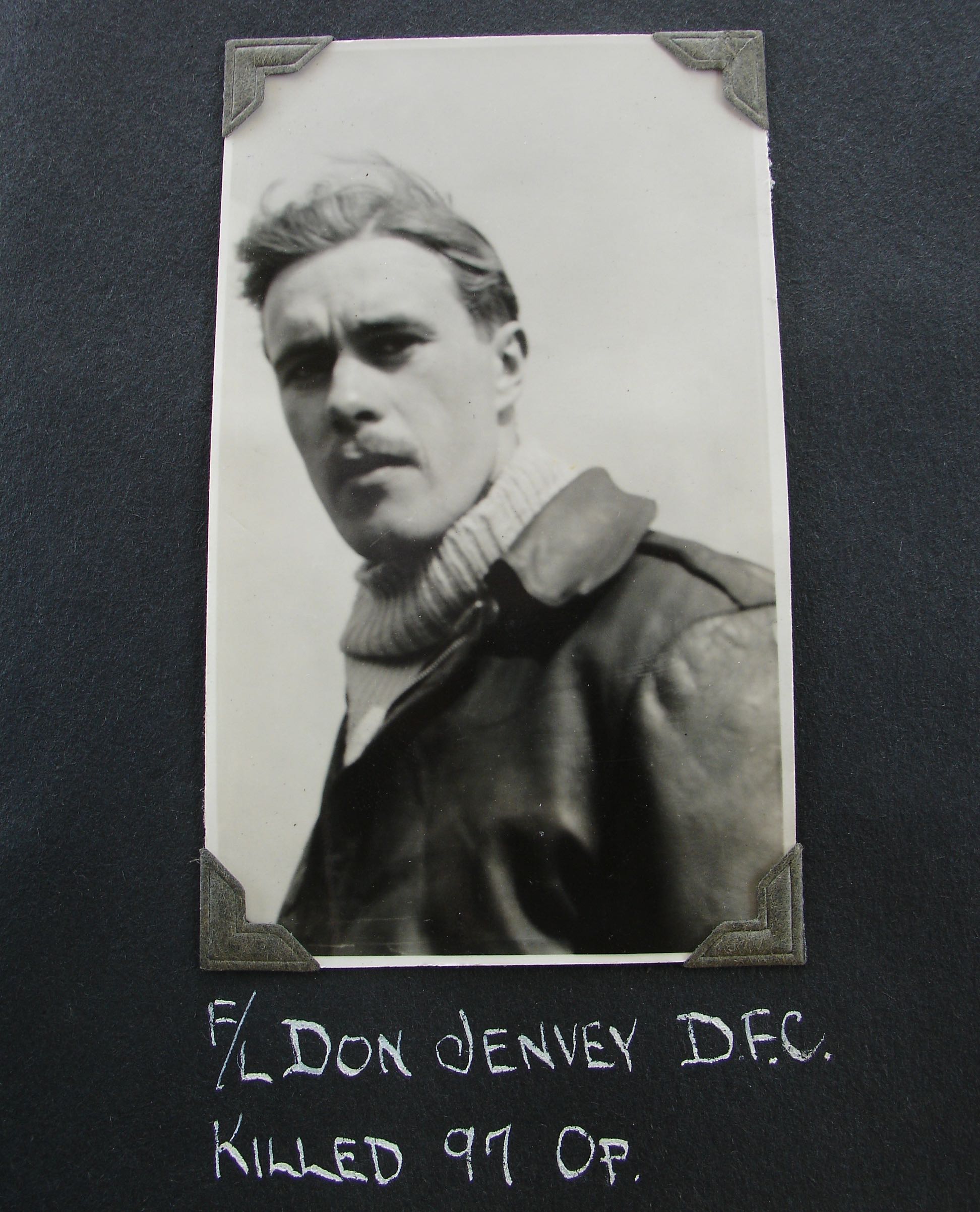

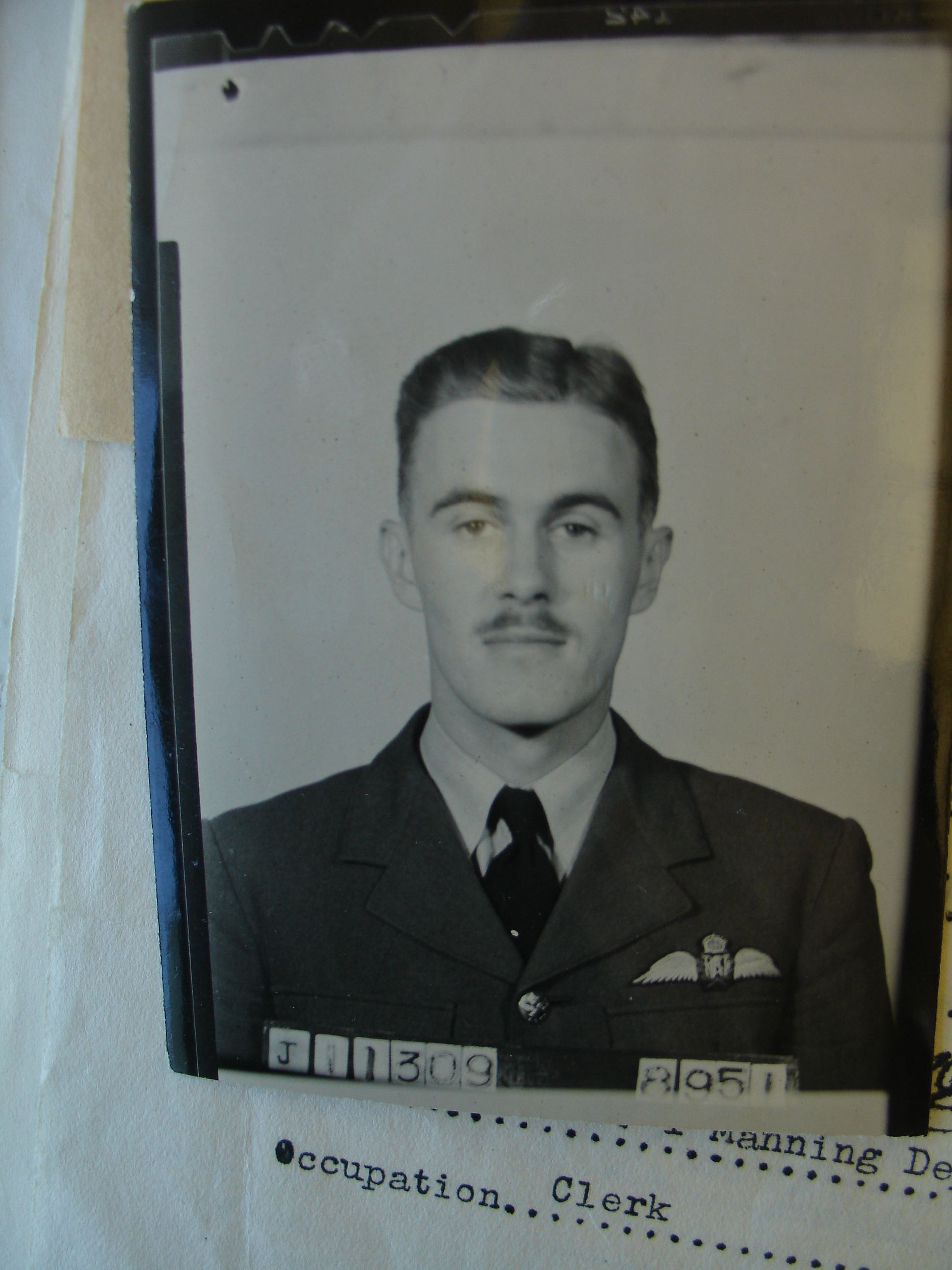

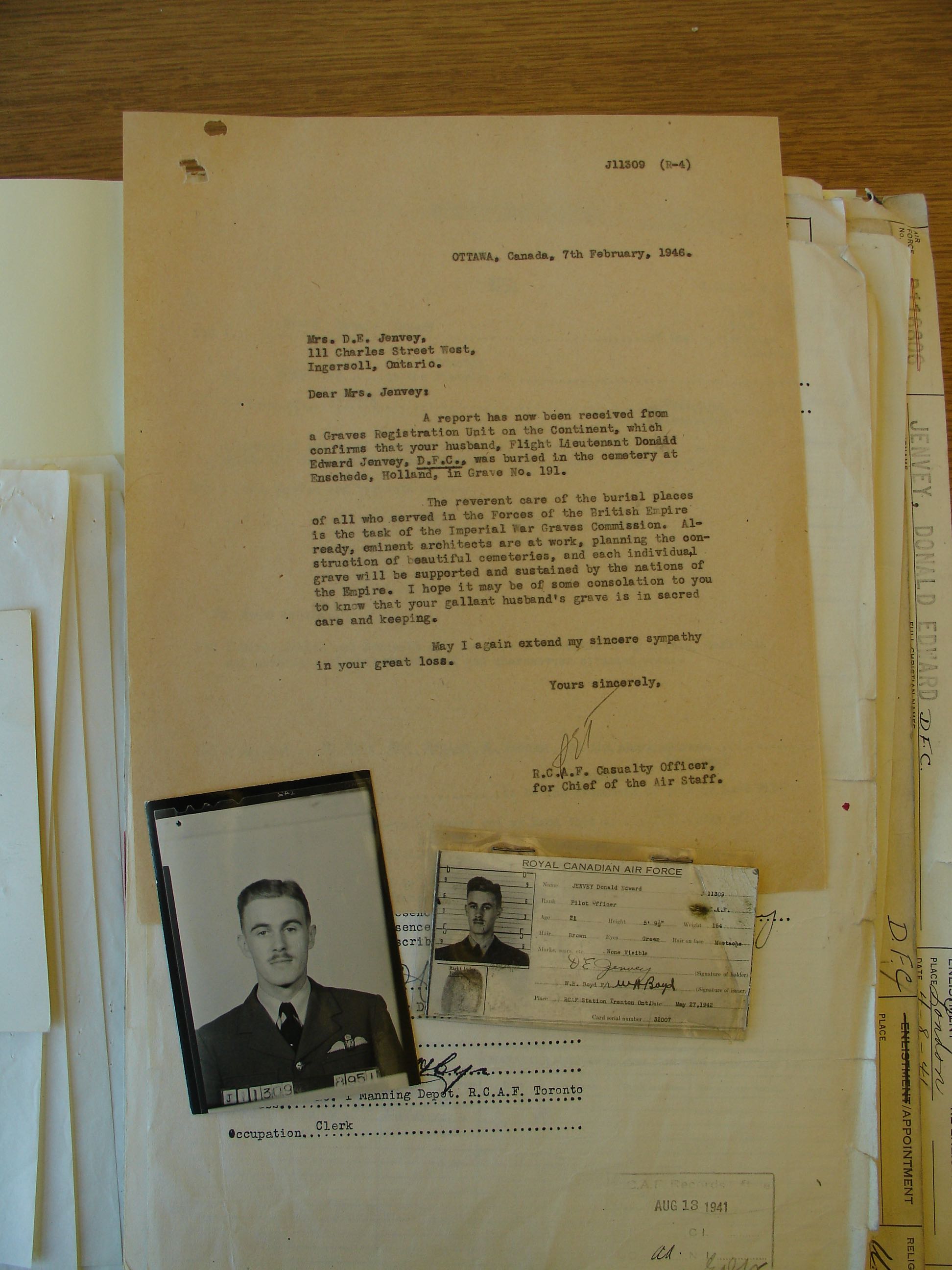

January 9, 1921 - March 25, 1945

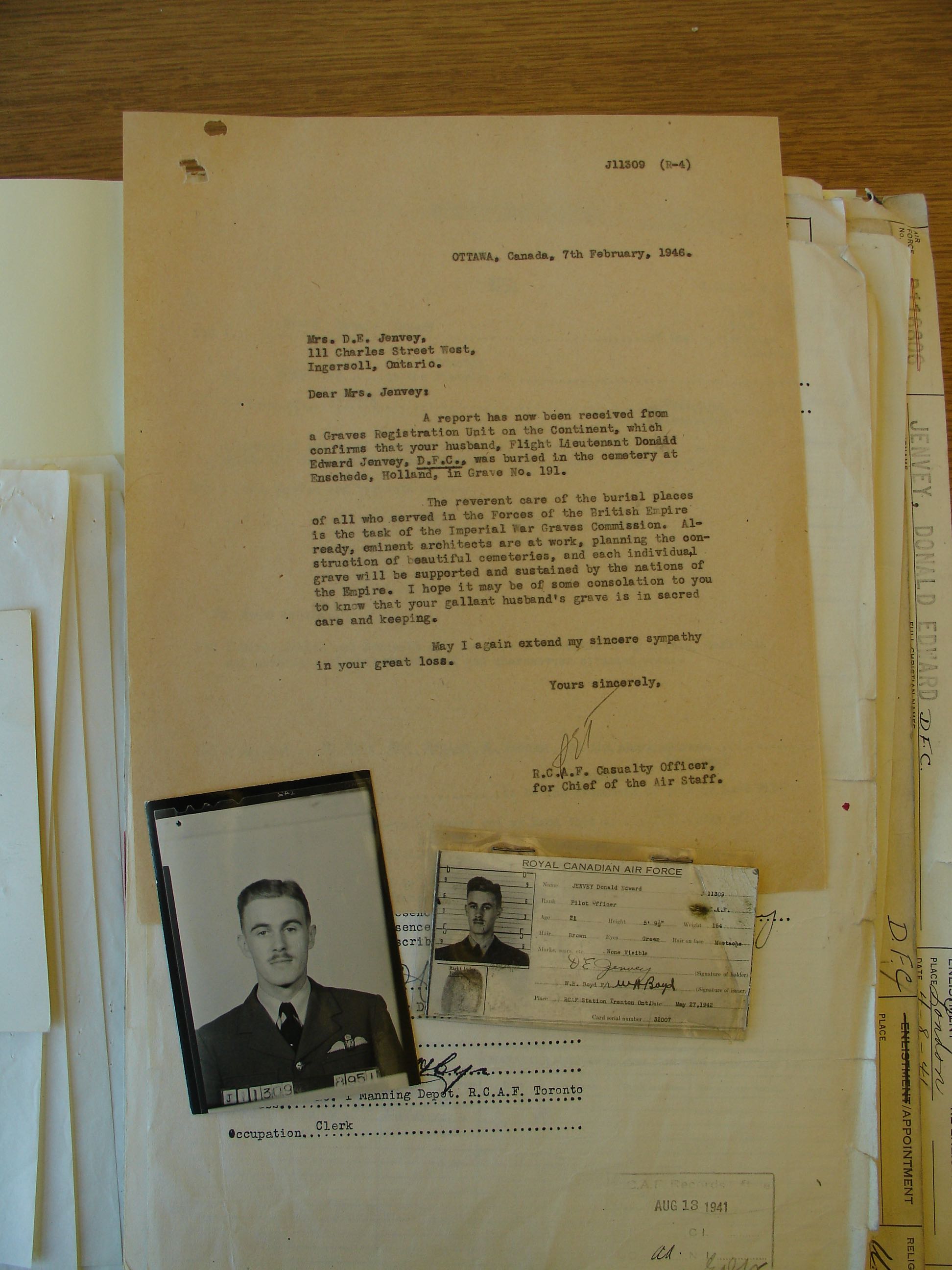

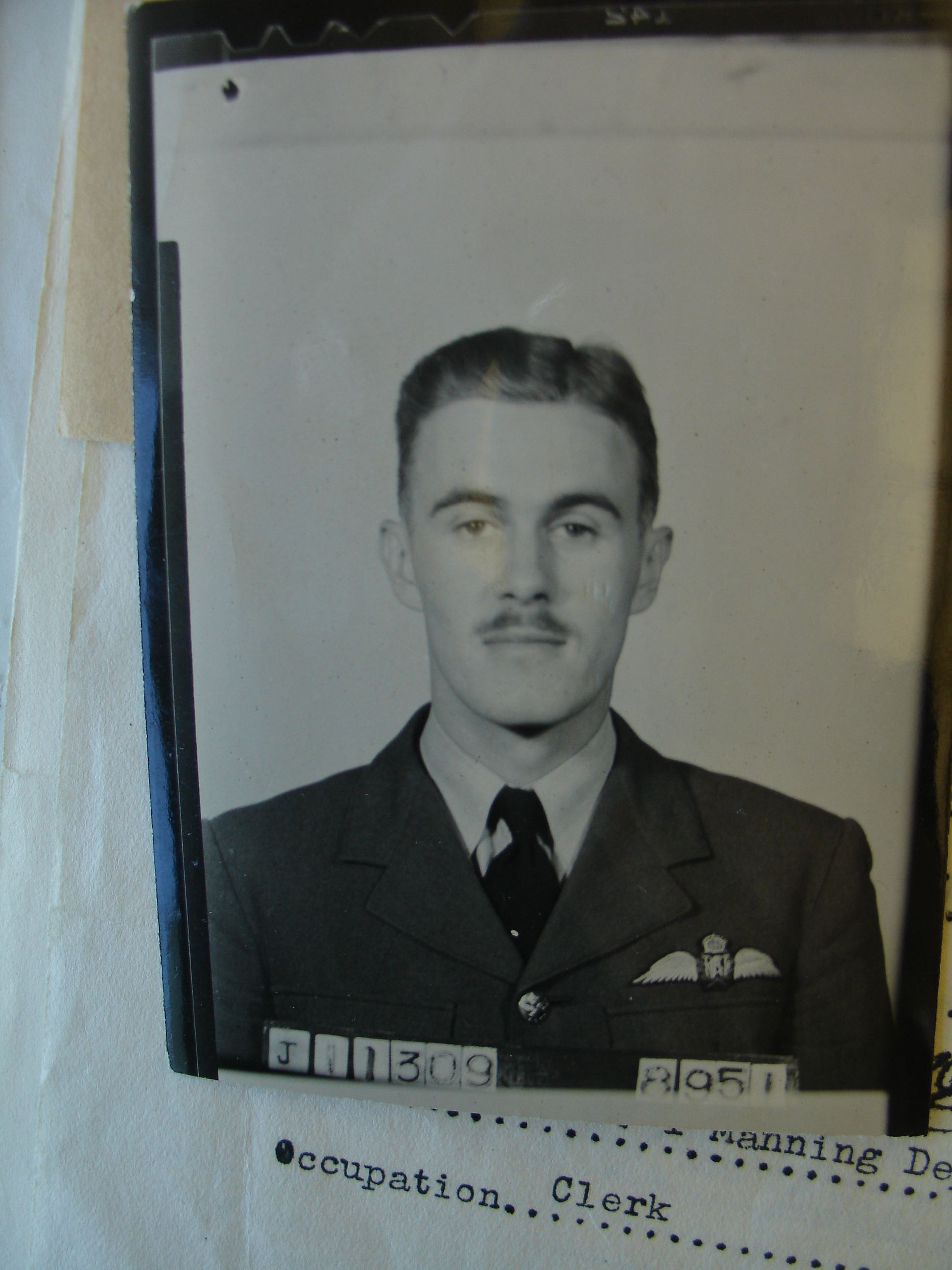

Donald Edward Jenvey was born to Earl Stanley Jenvey and Mary Eunice (nee Mitchell) Jenvey, in West Oxford, Ontario, residing in Ingersoll, Ontario. He married Beulah Marguerite (nee Chamberlain), also of Ingersoll. Together, they had one child.

Jenvey had written a letter to the RCAF in April 1941 requesting he be transferred to the RCAF from the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve where he had trained as a wireless operator. He said, “Surely with a world at war, you can find a place for one signals officer who wants with all his heart to serve his country.” He wanted to stay in the Air Force after the war to make it his life’s work. He then enlisted with the RCAF on August 4, 1941.

He received excellent evaluations, including “a very determined type of trainee. Knows what he wants and goes for it. Good Service spirit and plenty on the ‘ball’.”

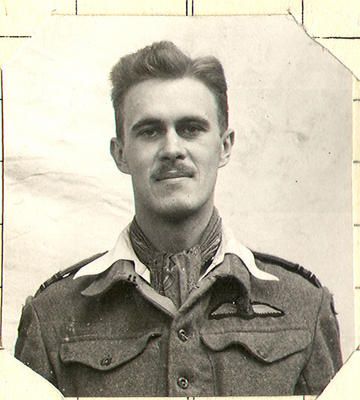

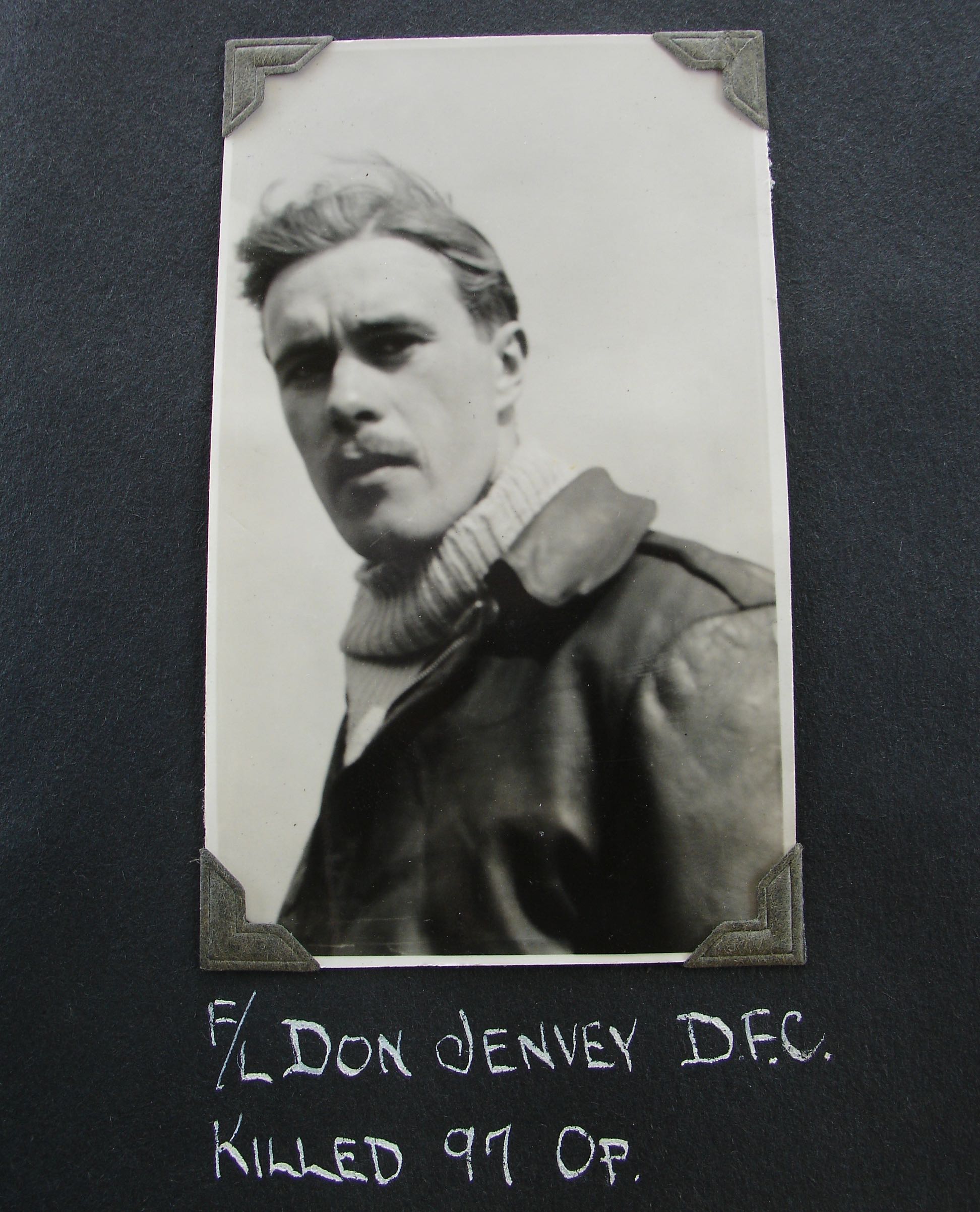

Royal Canadian Air Force veteran, F/L Captain-retired, Harry Hardy, 96, a resident of Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada, was a Typhoon pilot stationed in France, Belgium and Holland during the Second World War with 440 Squadron, part of the 2nd Tactical Air Force, 143 Wing. He is known as the ‘Pilot of the Pulverizers’ and was a good friend of Buck Jenvey.

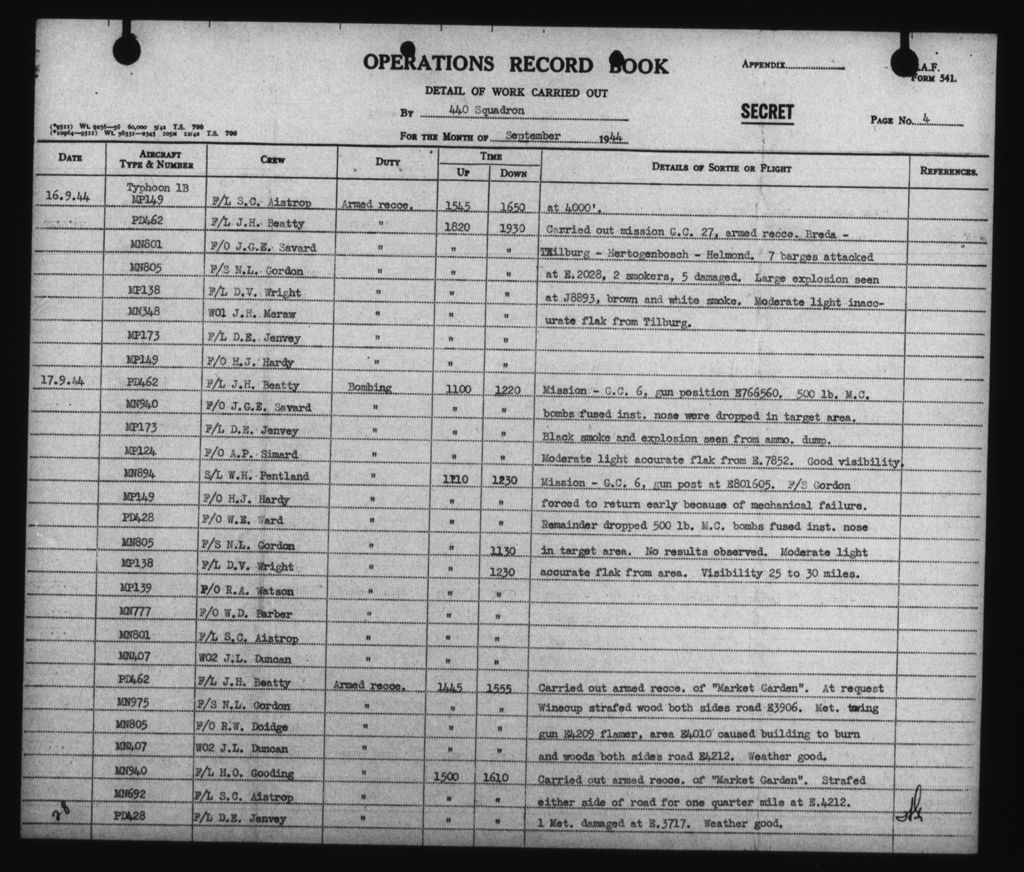

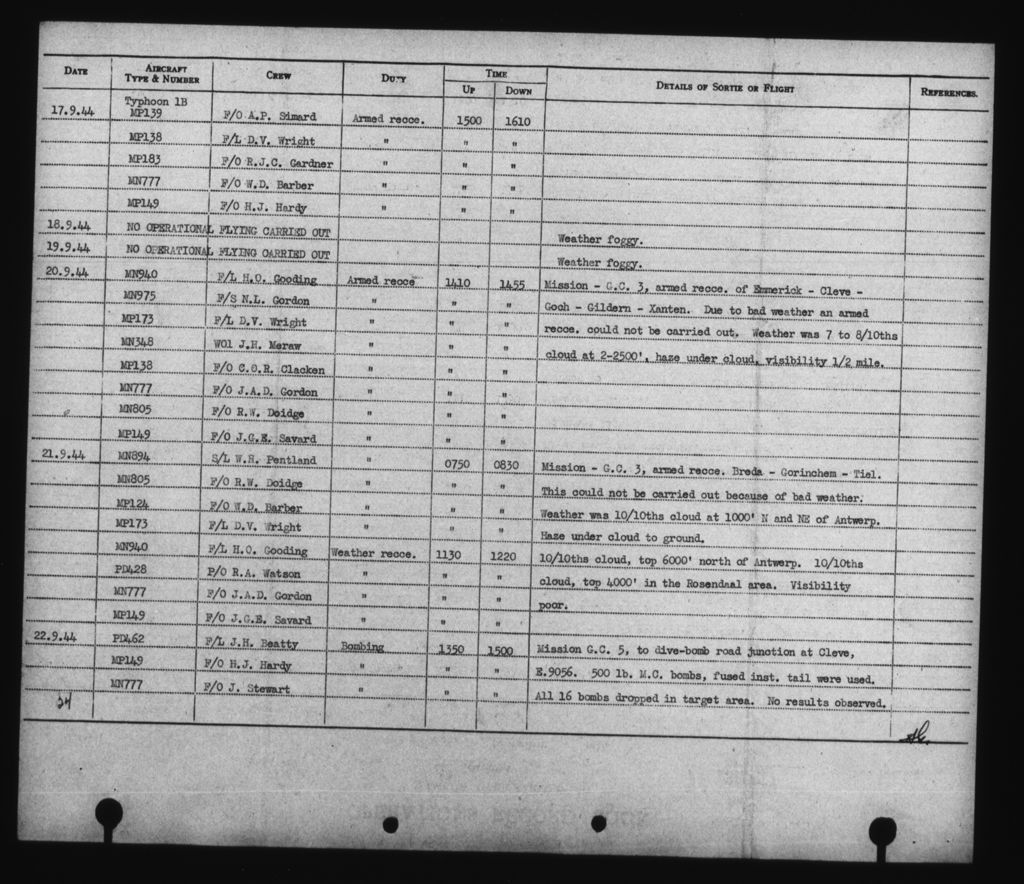

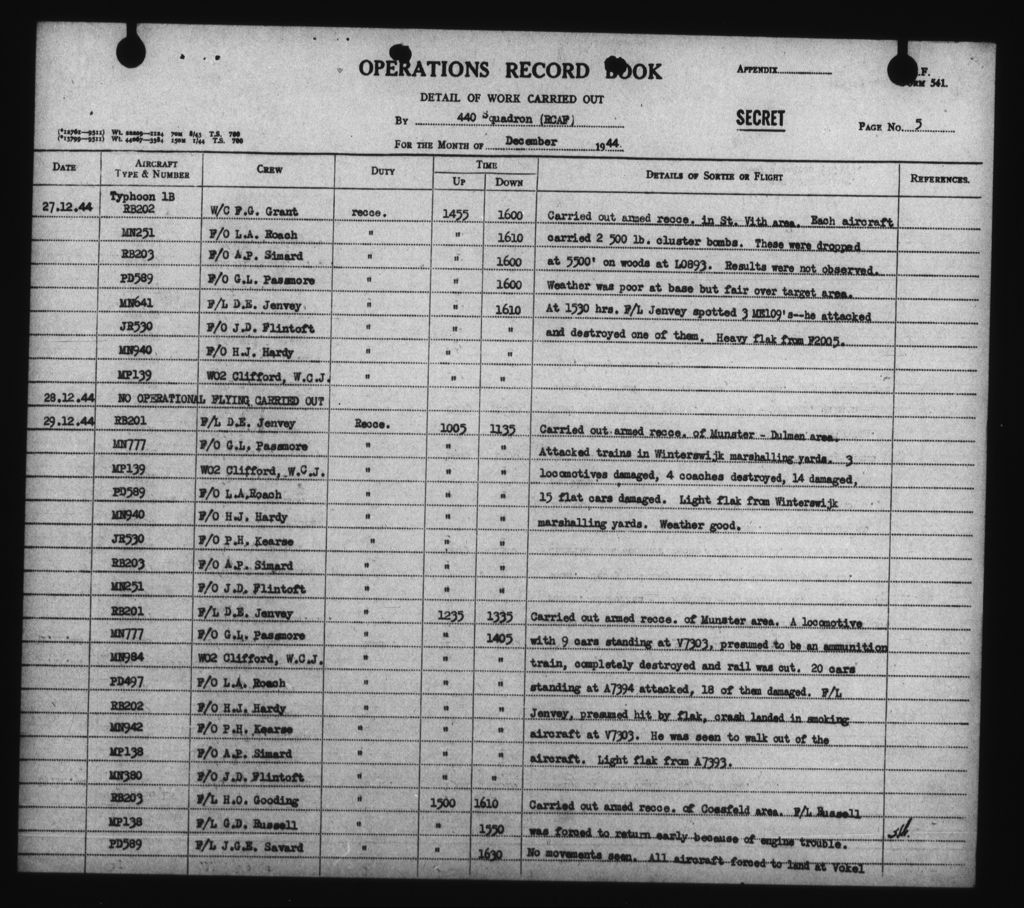

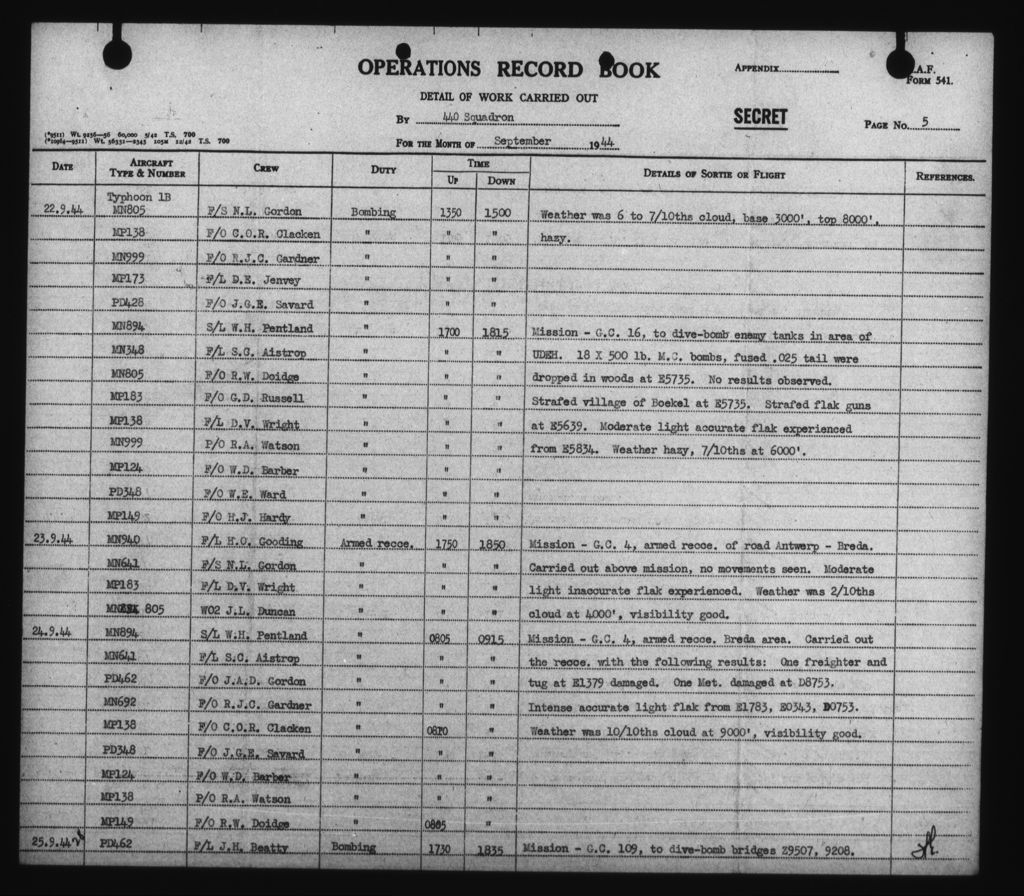

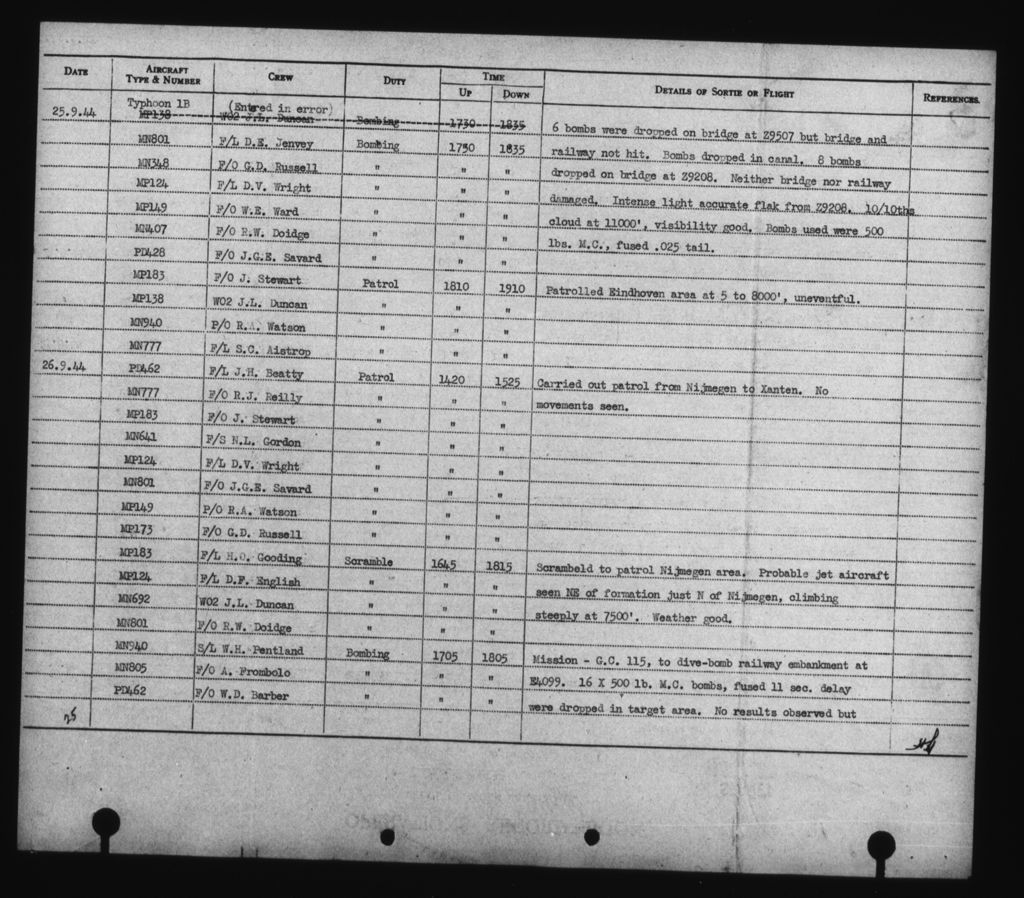

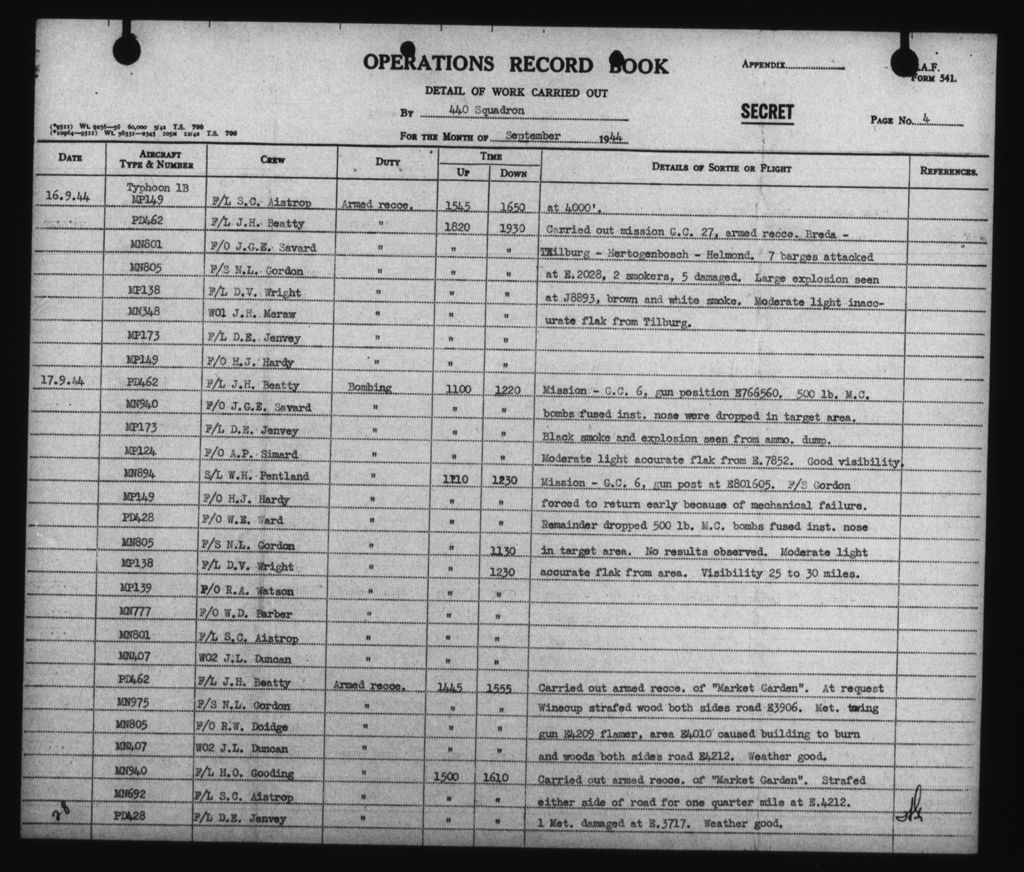

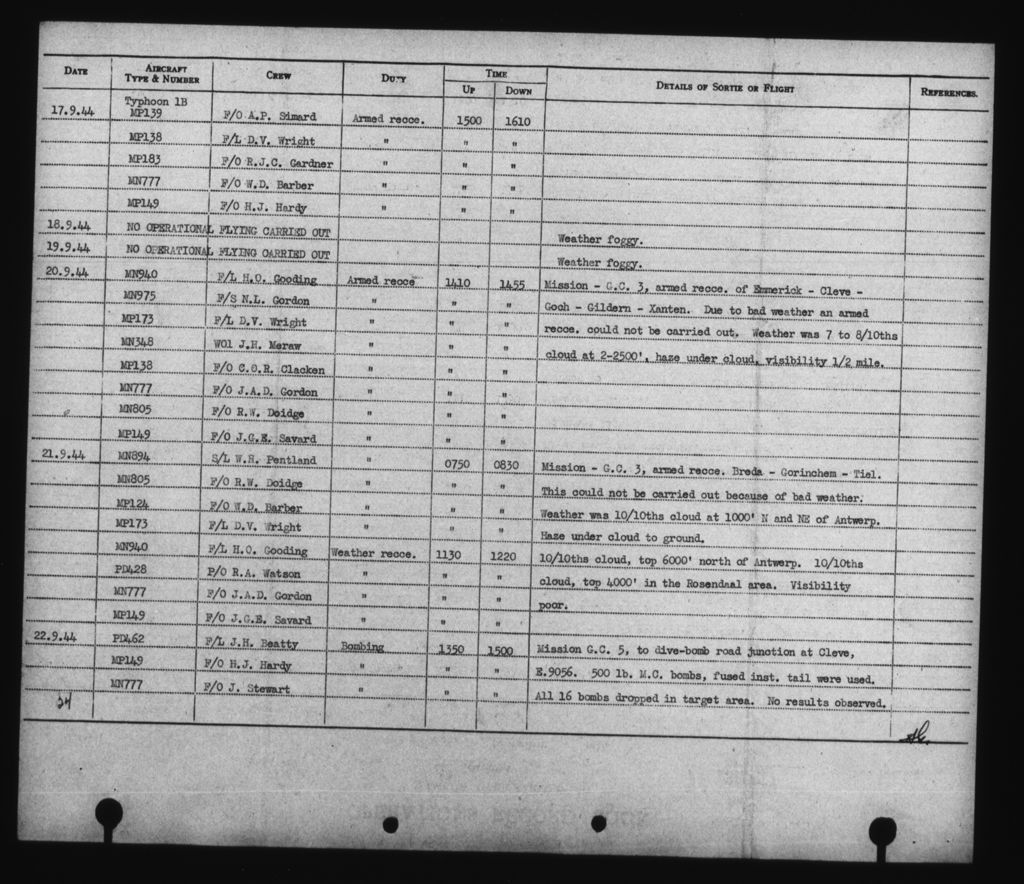

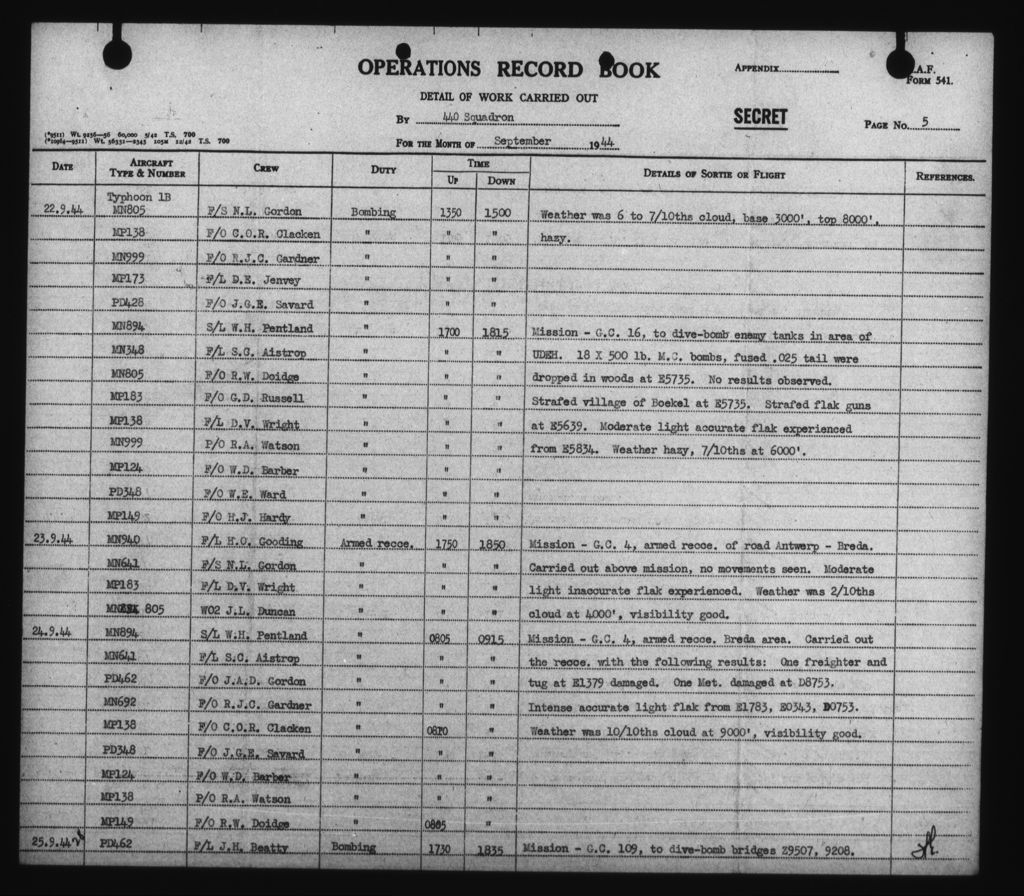

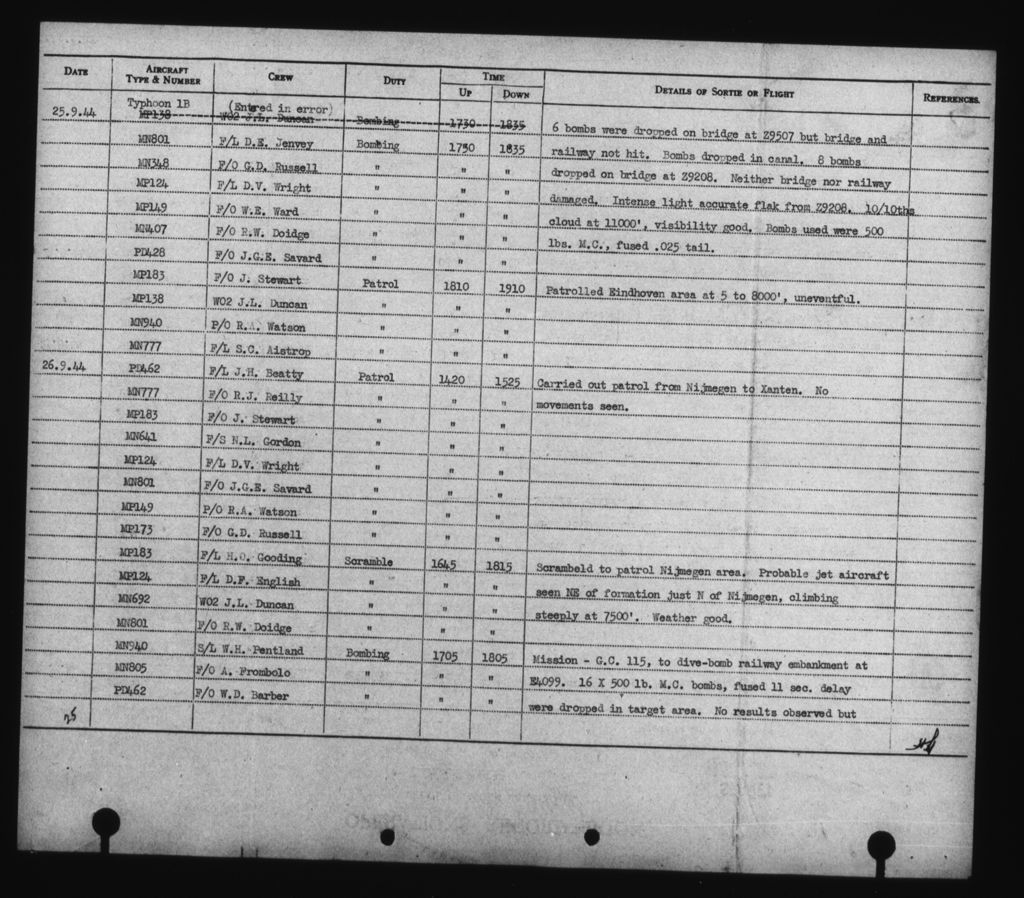

In the 440 Squadron Dairies, it was noted: “’A’ Party proceeded by road to B. 58 near Brussels, Belgium. Pilots left by air at 1800 hours going in two sections of 9. The section led by F/L H. O. Gooding ran into difficulty trying to locate Brussels, and on being unable to get a homing from Flying Control, returned, intending to land at B. 48 near Amiens. Bombs were jettisoned ‘safe’ and a rainstorm was encountered. No word was received from personnel at B.48 and B. 58 as to their whereabouts and all pilots were posted as missing, details unknown.” Over the course of the next four days, the pilots all made it back to their base.

Harry recalls this event in detail. He was fairly new with the squadron at this time.

“Hal Gooding, our leader, got us lost on our flight from Amiens to Brussels. We were to do a sweep. Officially, we were on an armed recce, and we were out looking for targets. It was pouring rain, we could hardly see. We were forced down low to stay under the clouds. I knew right then we were in trouble. Only Red and Blue Leaders had a map read on an op. The rest of the squadron’s job was to watch out for enemy fighters. The next thing I remember hearing was the CO saying, ‘Saffron Squadron Saffron Leader steer 270 degrees, land when you are running out of fuel.’ I knew we were over the front line as I saw the army’s red panels on the ground. I came to a large field full of cows where I dropped my bombs - they were unfused, so safe.”

Hardy continues, “I went down in mud in a newly ploughed field with the furloughs going the long way and put Pulverizer I down on her belly with my wheels up. We were taught to always go down with wheels up. That was the law!

“But Buck put his wheels down, as he was landing in a field. His brakes were no good and the plane slid, dropping into a gully. Luckily, the plane did not slip onto its back! It was a nice landing.”

Mrs. Jenvey received a letter in September 1944 letting her know her husband was safe, after having been reported missing. At that time, he, along with eight other Typhoon pilots ran short of fuel and had to make a forced landing. The official report stated: “PILOT UNABLE TO LOCATE BASE FORCE LANDED DUE TO PETROL EXHAUSTION.”

Hardy explains how after he landed, a French family came out to see what happened. They were happy to see a Canadian but were surprised I could not speak French!” The farmer took Hardy home, where the family ‘wined and dined me,” he says, and allowed him to sleep in one of the children’s beds. The next day, the farmer via bicycle took Hardy to an FFI (French Forces of the Interior) safe house. “Buck was there before me. They left us sitting there. I only knew him in passing, as I was a sprog. He had flown so many more ops than me.”

The men waited until an English speaking female doctor arrived. Hardy was wearing his blue battledress; Buck: khaki. Hardy says, “I did not like khaki, but I guess it made for better camouflage.” The doctor determined neither were spies and the men were taken through to the American line where they hopped onto a truck. “We were kicked out when the truck got to its destination, so we had to walk and hitchhike for three days, travelling from Bohain to Brussels.” It was a 148-kilometer trip. “We stayed at a hotel in Charleroi and the people were keen to meet us, as they had just been liberated. We were heroes to them.” Hardy and Jenvey both carried cameras, taking photos along the way.

Buck and I became good friends during our experience of being lost. He was a very experienced pilot with many ops already to his credit. He asked me if I wanted to be his wingman and I flew in that position whenever possible. I am sure his guidance had something to do with me surviving my first ops while I gained experience and savvy on how to stay alive.”

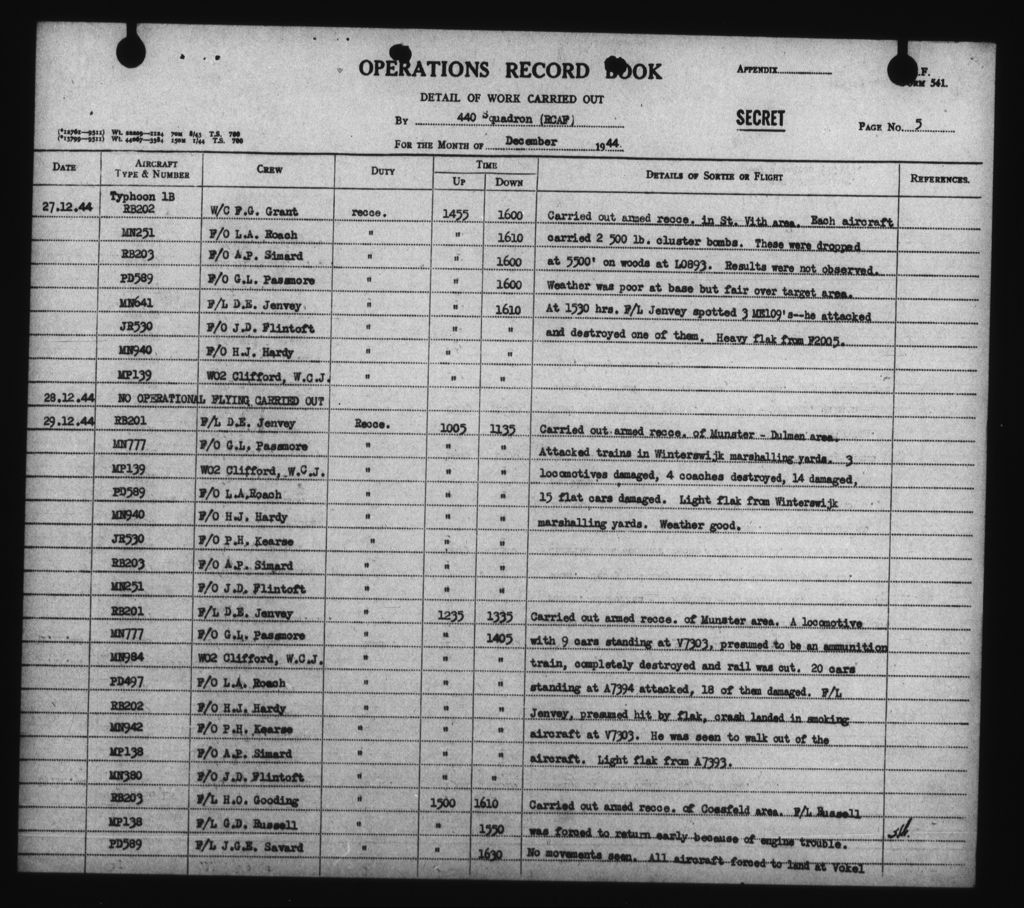

But on December 29, 1994, "my good friend and mentor was hit. We were strafing a train when the car Buck was strafing blew up and he flew through all the debris in the air. Some of it went into his oil cooler and he came out the other side streaming coolant. He force landed in a field, got out and was running towards a treed area. I flew down low over his plane; he stopped, turned around and waved to me. This image has always stayed with me. The plane in front, the bushes behind and him waving to me.”

Hardy picks up the story. “Buck managed to avoid capture until late March when the Germans finally caught him and shot him.” Hardy speaks matter-of-factly about the death of his friend. “We were losing people all the time. Three months had gone by. We got used to it. Every week, we’d lose a guy and another would take his place. We had just crossed the Rhine the day I heard Buck had been shot. March 25, 1945. This was the day after my last op. Buck managed to avoid capture until late March when the Germans finally caught him and shot him.” Hardy speaks matter-of-factly about the death of his friend. “We were losing people all the time. Three months had gone by. We got used to it. Every week, we’d lose a guy and another would take his place. We had just crossed the Rhine the day I heard Buck had been shot. March 25, 1945. This was the day after my last op.”

One was a statement with official details, but also a seven-page letter written on April 14, 1945 by 38-year-old Pieter Scholten of Delistraat 54, Enschede, Holland to Jenvey’s widow.

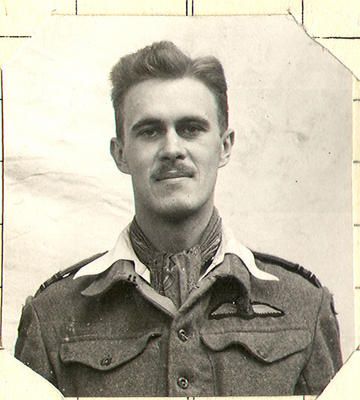

Mr. Scholten described how the Canadian pilot escaped his burning aircraft and fled into Holland, where he hid in Oldenraal with a farmer and his family until March 17th, 1945. Then the Dutch Underground brought him to Enschede. The Scholten family hid the pilot in their home until March 24th, where stories and tales were shared. Buck told Mr. Scholten of evading German soldiers. Both men had young sons. Both used the same razors and shaving cream. Mrs. Scholten nursed Buck’s scurvy. Buck showed the family his watch, ring and silver-plated pencil that he had received from the people in Oldenraal, plus his green fountain pen. On March 21, a photo was taken of him and false papers created. He was to become a deaf mute. On March 22, Buck was taken to Hengalo, then brought to another man, who turned out to be a German spy. They were to have taken bicycles to another meeting place via Emmerik, but there were mechanical troubles with the bikes. The letter describes Buck Jenvey’s arrest, and the fight against three men in the German car with the civilian driver grabbing the gun and fatally shooting Buck. Mr. Scholten mentions that Buck took the moment to fight when a squadron of Typhoons was in the air. A package of Buck’s belongings was returned to the Scholtens.

Enschede was liberated on April 1. On April 12, the Scholten family and others witnessed the exhumation of Jenvey at which time several of his belongings, sewn into his clothing were retrieved. The letter concludes by inviting Mrs. Jenvey and her son to visit, as they would hold a place of honour at the Scholten’s home.

Hardy says, “After reading the letter, it was nice to know what really happened. Of the 27 pilots killed on our squadron, Buck is the only one buried in Enschede Eastern Cemetery.” Buck’s headstone reads ‘His work well done, His battle won, He has gone to his reward.’ “During the 2-minute silence on Remembrance Day, November 11, I always see Buck standing there waving to me.”

Additional information about Buck Jenvey can be found in Typhoon and Tempest by Hugh Halliday. On April 15, 2013, Scott Gillies, for an Ingersoll newspaper, wrote the article "Route to the Past" about Donald Edward Jenvey.

LINKS: